Music is more than just entertainment. It shapes the very quality of our lives—the fabric of reality itself. Here’s how sacred music can call forth the raw magic of being and help us learn who we really are.

The first sounds a child hears are the rhythms of his mother’s heart. At birth, he breathes deep and cries loud. To the child, all things are musical… and as we grow older, music often helps us return to that childlike fascination. It’s primal, elemental, something beyond words even when it employs them. Music invokes a transcendental state—literally “crossing up and across” from one state to another. Is it any wonder, then, that faeries adored Thomas the Rhymer, or that aliens spoke to humanity through song in Close Encounters of the Third Kind? The harmonies, vibrations, beats and intervals of sacred music guide the waves of Creation itself.

“Music,” said the philosopher Boethius, “is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired.” Rooted in the sounds of nature and the echoes of the spirit, music remains one of the most significant human arts. Music stirs emotions, rouses ghosts, seduces elves, and temps gods, men and devils to dance. Inspiring “peak experiences,” it can bring us ex stasis: “outside ourselves.” Music has been said to move stones, shatter walls and foment revolutions. Our modern world is filled with music… and yet, amidst all that sound, the deeper significance of this art is often lost.

RELATED: Here’s 10 Epic Albums That Will Awaken You to Magick & the Occult

It’s easy to take music for granted these days. TVs, iPods and passing cars blast music into every corner of our lives. Still, we share a problematic relationship with it, too. It’s so pervasive, so commercial, so very often junk that music become literally meaning-less. We can rip symphonies from CDs, buy ‘em for a buck or two, link remixes to our Facebook pages, or simply download the pleasures of kings for free off the Internet. What was, until recently, a unique transformative experience has become “data” in our world—endlessly replicable and infinitely collectable.

Speaking personally, I have more music on my iPod right now than most people would hear in their lifetimes a century ago… and yet, I constantly crave more of it. We’ve probably got that in common, you and me—and we’re in good company there. Like anyone who gets too much too easily, though, we lose track of how precious music is. To us, its magic has become mundane. We use music for damn near everything. What, then, in our world does it MEAN? When transcendence is cheap, what value does transcendence have? How many of us are willing to even ask that question, much less willing to find out?

Characters and stories from my book-in-progress Powerchords: Music, Magic & Urban Fantasy reveal the deeper levels of sacred music—not the soundtrack of our daily buzz, but that transformative and all-too-fleeting burst of Other. The paradox, though, is that music is so meaning-full to such people and adventures that it assumes day-to-day roles, yet never becomes routine. A professional pianist practices scales and exercises for hours each day precisely because music matters so much to her. The glamour of a musical life is part of Powerchords’ appeal, as well—you wouldn’t be reading these words right now if you didn’t want to vicariously rock out. Let’s look, then, at the interplay between music, magic and the mundane world that, for better and worse, has brought us Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, American Idol, hip-hop fashions and, of course, Powerchords…

It wasn’t until records and tapes and all that—that you could buy what you think is music. But that’s not music—that’s just plastic. Music is in the air. It always has been in the air, always shall be in the air. – Ian MacKaye

From the Beginning

Creation, as it’s often said, begins with a single sacred birth-sound: a Kabbalistic thunderclap, a “Big Bang,” or the divine chant proclaiming “Let there be light.” In Hindu and Buddhist teachings, this sound is OM, the Primary Vibration from which all things come. According to esoteric music theory, Om resounds throughout Creation, transcending past, present and future, uniting everything and forming the ineffable root of being. Echoes from this primal sound ring out as cosmic harmonies—the so-called “Music of the Spheres.” Explored by Chinese sages and Greek cosmologists, these reverberations set the tone for all living and unliving things.

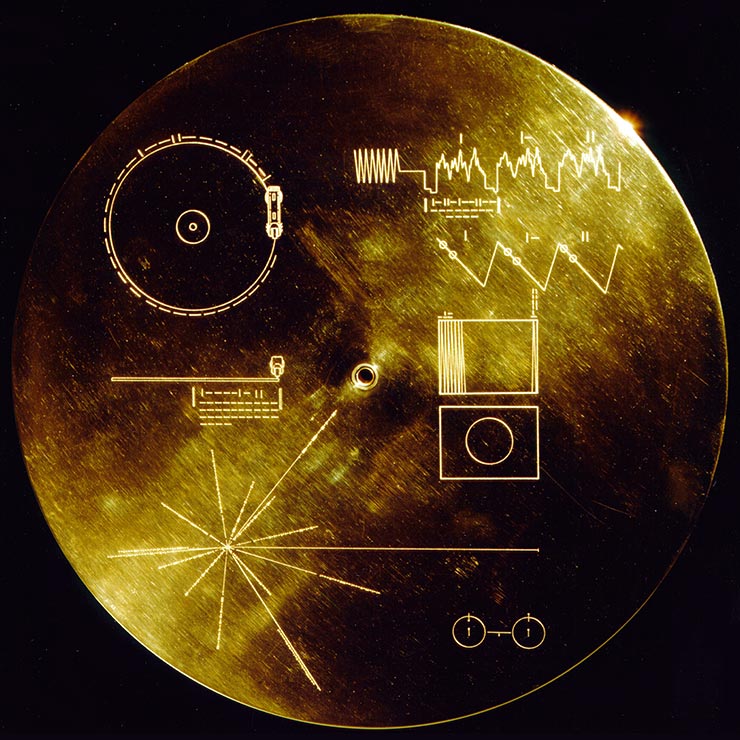

Throughout most of human history, music remains ephemeral. The idea of hearing a song from some dead person or distant land is literally unimaginable. Music exists in the here-and-now, fading to memory once the sound waves grow still. Until recording technology gets invented around 1890, music lives and dies in the moment of performance.

RELATED: Die Antwoord’s “Pitbull Terrier” and Occult Social Control

And yet, in many cultures, music forms part of daily life. Massai villages, Iroquois councils and Celtic countrysides echo with song. Dance is a fundamental skill for French courtiers, Siberian shamans and Sufi seers alike. Chanted voices bring Buddhist, Jewish and Catholic mystics closer to their gods. Languages—Hebrew, Greek, Arabic, Sanskrit and more—hold musical significance as well as linguistic practicality. Fleeting as it might be, sacred music expresses the human experience.

Although the first mortal harmonies are soon lost to time, the metaphysician Hans Erhard Lauer will someday envision them as legacies of sacred music from the fabled Lemurian Period. This “wordless primordial song” predates human speech; according to the psychic Rudolf Steiner, Lemurian music occurs in intervals of ninths, not the intervals of eighths that eventually give us the term octave. “Anyone in those days,” writes Lauer, “who either heard or chanted this primordial song would have been transported into the spiritual cosmic world among the gods… the sound was an echo in man of that supersensitive music that sounded in the spiritual worlds, as the gods revealed their joys and sufferings… in sounds of jubilation or songs of lamentation.”

Eons later, the people of Atlantis supposedly perfect a musical technology that’s tuned to successive sevenths. This technology allows Atlantian adepts to build pyramids and walls of cyclopean size. Misuse of that technology, however, supposedly sinks the continent, scattering its children across the primal world. True or not, this myth imparts a powerful lesson: For all its marvels, music holds the potential for catastrophe.

Spirits in the Material World

Music’s historical origins are pretty humble. Songs begin as imitations of animal sounds, instrumentation as slaps across one’s leg or blows on hollow logs. The oldest apparent musical instrument (a vulture-bone instrument roughly 35,000 years old and thought to be a Neanderthal flute) displays a desire to create sounds beyond the human range. The earliest known human song is transcribed in Mesopotamian cuneiform at roughly 1400 BCE. By then, however, several cultures have already developed systems of tuning and techniques of instrumentation. Egyptian paintings and Hebrew scriptures describe pipes, flutes, drums, chimes, stringed instruments and musical rites. In every known human culture, sacred music soon holds a place of honor among men, gods and spirits alike.

Music is the harmony of heaven and earth, while rites are the measurement of heaven and earth. Through harmony, all things are made known. – The Li Chi

As human civilizations rise, each culture refines new musical arts. The courts of T’ang Dynasty China maintain over a dozen ritual orchestras, consisting of five to seven hundred musicians each. Jerusalem’s temples feature devout choruses for the chanting of scripture. Majestic Persia boasts a dazzling musical tradition that ranges from percussive symphonies to plaintive flute drones and haunting a cappella songcraft. And in Greece, the sage Pythagoras establishes the sacred science of musicology that will guide western musical theory to the 21st century and beyond. Conceived as a reflection of the Music of the Spheres, the Pythagorean school employs songs as therapy, medicine, mathematical exercise and spiritual devotion. As Aristotle notes, the Classical Greek ideal of sacred music “has thus the power to form character, and the various kinds of music based on the various modes, may be distinguished by their effects on character.”

In ancient China, the health of the kingdom is gauged, in part, upon its music. Chroniclers credit Ling Lun, minister to the legendary Yellow Emperor Huangdi, with the invention of music somewhere around 2300 BCE. Observing six male and six female phoenixes, he cuts lengths of bamboo and carves them into flutes. Imitating the phoenix cries, Ling Lun plays notes that perfectly balance the energies of yin and yang. Refining those six tones down to five, the Yellow Emperor soon has bells cast to mirror these notes; thus, the foundations of earthly harmony are created.

According to the Shu King, the venerated Emperor Shun travels through the territories of China around 2000 BCE, gauging their stability by the pitches and notes of their sacred music. Utilizing the eight kinds of musical instruments approved by ancient Chinese philosophers—stone chimes, bell chimes, zithers, pipes, drums, reed mouth-organs, globe flutes and the wooden “tiger box”—the emperor orders musicians play local folk and courtly songs. Their performances are then checked against the five harmonious tones, particularly the huang chung (“yellow bell”), the pitch mirroring the perfect harmony of Cosmic Sound. If the arrangements, compositions or performances seem overly passionate or unorthodox, Shun knows that trouble will soon follow.

The man who knows nothing of music, literature or art is no better than a beast. – Hindu saying

Yulunga (Spirit Dance)

Beyond the courts, energetic folk music traditions flourish in rural towns and villages. Disreputable by the idealized standards of nobility, these musicians employ simple instruments, unaccompanied vocalizations and earthy themes. Such musicians are either self-taught or schooled by talented elders. Such mastery, though, can be difficult to learn… and so, aspiring musicians sometimes employ “shortcuts,” making deals with otherworldly tutors that will later become familiar to the likes of Paganini and Robert Johnson.

RELATED: 5 Trickster Gods That Caused Total Chaos (and Got Away With It!)

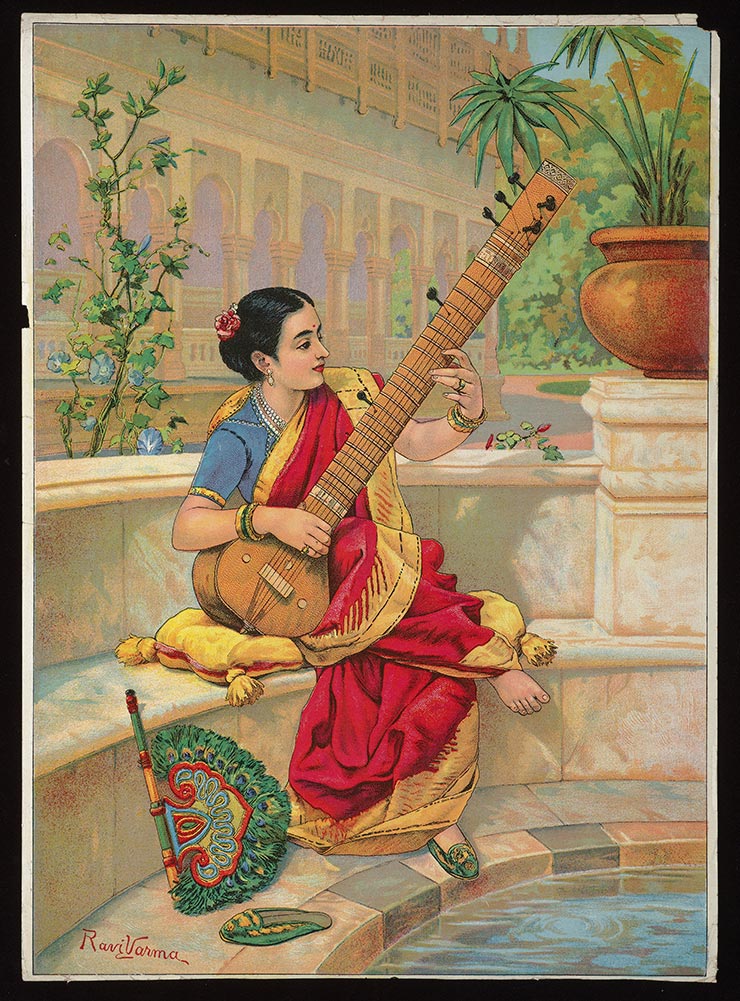

Many traditions consider sacred music to be the bridge between humanity, nature, and the realm of gods and mysteries. The god Indra gives Sangreet—the threefold sacred art of Indian vocal music, instrumental music and ceremonial dance—to the mortal Narada in order to entice people away from wickedness and distraction. In a similar vein, Maheo the Creator grants the Sun Dance and its music on to the Cheyenne hero Horns Standing Up, to save his people from starvation. Other beings, though, are less altruistic in their musicality. Lovesick Pan crafts his pipes from the body of Syrinx, a nymph who turns herself into a bed of reeds to escape his attentions; Pan also blows a conch shell in order to spread “Pan-ic” among the enemies of his Arcadian worshippers. Elves, meanwhile, lure curious humans to the woods with song, and then—depending on fey whims—seduce, kidnap or devour them. Coyote’s cry leads young fools into the wilderness, sometimes to disappear forever. Angels of the Judeo-Christian god sing endless hymns to his glory, while their fallen counterparts scream cacophonies (“infernal sounds”) deep in hell.

Some mortals, though, like Orpheus, turn sacred music to their advantage; charming his way past the barriers of death, he lives a glorious, tragic, Behind the Music life and then dies a glorious, tragic Behind the Music death. (The term “tragedy,” incidentally, comes from the Greek word tragōidia—“goat song.”) Thomas the Rhymer likewise beguiles faeries, mortals, animals and monsters; his life, too, becomes the stuff of legends. Brulé lore speaks of a young hunter taught by Wagnuka, the Woodpecker, how to make and play a flute; that musical gift soon helps him became a successful lover and a prosperous chief. It’s said that even Jesus of Nazareth danced at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1-11). For mortals, gods, and everyone in between, music giveth, and music taketh away.

The element of magic reverberates through the musical arts. A person who can raise such power, after all, must be in touch with the Otherworlds. Native American “secret songs” flow from vision-dreams; Orpheus himself is born to Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry. Indian men play flutes to adore (and imitate) Krishna, whose tunes summon the beautiful and amorous gopis. In more austere fashion, Catholic monks and nuns chant angelic chorus prayers. Medieval Abbess Hildegard von Bingen weaves haunting songs Christ’s name, while Satanic witches dance to the Devil’s tune. A fine singing voice can get a boy castrated (to preserve it) or a girl burnt alive (to destroy its seductive potency). Either way, sacred music holds power far beyond simple sounds or words.

Songs that nurture may also destroy. The awful Dipaka ragaimmolates anyone who sings it; to test its power, the Emperor Akbar orders the bard Naik Gopaul to perform that raga. According to lore, the singer stands neck-deep in a river, but the song still burns him alive from the inside out… and boils away the river as well! Such are the dangers of musical fame…

How to Create Your Own Sacred Music and Artwork

Interested in applying sacred techniques to supercharging your own music, art, or even turning your life into an artistic masterpiece?

Check out our course on Magick and Art, in which you’ll learn how to apply the sacred techniques of some of the greatest musicians and artists in history to making your own life a masterwork.